The best global strategy for the US may be the one that won the Cold War

By Commander Philip Kapusta and Captain Donovan Campbell

THE EVENTS OF Sept. 11, 2001, brutally announced the presence of an enemy seemingly distinct from any our country had faced before. Unlike previous adversaries, such as Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, or the Spanish monarchy, this new enemy was difficult to define, let alone understand. It was not motivated by causes that an avowedly secular government could easily comprehend, and it took an amorphous yet terrifying form with little historical precedent.

Our leaders responded to this new threat with dramatic changes. In the largest government reorganization of the past 50 years, the Department of Homeland Security lumbered into existence. A new director of national intelligence was named to oversee America's vast intelligence apparatus, and the defense of the homeland was made the military's top priority. Most dramatically, the United States announced - and then implemented - an aggressive new policy of preemptive war.

Yet, with the seventh anniversary of 9/11 approaching, it seems clear that policy makers have not responded particularly well. Islamic extremists are gaining strength, while America finds itself increasingly isolated in the world. The coalition of the willing, never overly robust, is now on life support. In the Middle East, the Islamist parties Hezbollah and Hamas have enough popular support to prosper in free and fair elections, and Al Qaeda is adding franchise chapters in North Africa, the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, and elsewhere. Our most prominent post- 9/11 action remains the Iraq war, which has arguably failed to improve America's national security even as it has strengthened the position of our sworn enemies in the government of Iran.

Underlying these global setbacks is a core problem: The United States has yet to formulate a holistic strategy to guide the prosecution of our new war. We have not articulated a clear set of mutually reinforcing goals, and we have not undertaken a consistent set of actions designed to achieve our aims even as they demonstrate our national values. Indeed, we have not even managed to properly identify our enemies; despite the rhetoric of the past seven years, America is not at war with terror, because terror is not a foe but a tactic.

Blundering forward, we have squandered the swell of global good will after 9/11, punished our friends, and rewarded our enemies with shortsighted, even self-destructive, tactics.

Yet what we face today is not wholly novel: It is a war of ideas, mirroring the Cold War. Like the Communists, violent Islamic extremists are trying to spread a worldview that denigrates personal liberty and demands submission to a narrow ideology. And, as with the Cold War, it must be our goal to stop them. The United States should therefore adopt a new version of the policy that served us so well during that last long war: containment.... Drawing heavily from articles written by the American diplomat George Kennan, the landmark National Security Council Report 68 (NSC-68) outlined a strategy of containment that served as the core of American foreign policy for every president from Truman to Reagan.

Presciently, NSC-68 identified the essential clash between the United States and the Soviet Union as one between diametrically opposed ideologies. On the Soviet side was a dogmatic belief system that demanded absolute submission of individual freedom and sought to impose its authority over the rest of the world. On the American side was an ideology premised on the overriding value of freedom, a system founded upon the dignity and worth of the individual. This ideology relied upon its inherent appeal, and did not aim to bring other societies into conformity through force of arms.

The policy of containment represented a tectonic shift from the military-centric, unconditional-surrender mentality of World War II.... containment did not define success as the military defeat and unconditional surrender of the Soviet regime. It had more modest ambitions: geographic isolation of the communist belief system and slow change over time. By fighting a global struggle for influence, the thinking went, America could avoid a costly full-scale war against the Soviets.

...The path dictated by NSC-68 was not a straight line to the collapse of the USSR, but the strategy proved remarkably effective. Communism expanded outside of its containment zone in a few instances, but, for the most part, the United States and its allies successfully implemented the indirect approach recommended by NSC-68. When the once mighty Soviet empire imploded in 1991, it was almost precisely as NSC-68 had predicted.

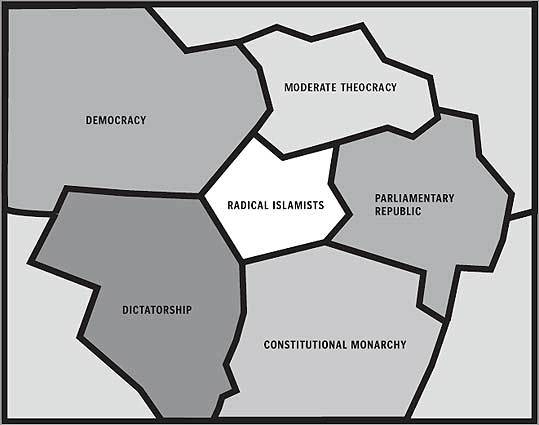

...Strikingly, if one replaces 'communism' with 'Islamic extremism' and 'the Kremlin' with 'Al-Qaeda,' NSC-68 could have been written in 2002, not 1950. Like communism, Islamic extremism lusts for political power, in this case through the restoration of the caliphate and the imposition of Sharia law on all peoples. Indeed, language from NSC-68 rings eerily true today - it described the Soviets as 'animated by a new fanatic faith, antithetical to our own.' Al Qaeda and its ilk are the latest in a long line of narrow ideologies that claim to provide the only true answer to life's existential questions. And as with Soviet communism, the idea has a geographic nucleus.

Our task now is to envelop this nucleus with prosperous, stable countries whose inhabitants are free to choose their own beliefs. Working from the outside in, the United States must partner with nations on the periphery to help them build a stronger middle class, enhance their education systems, improve basic health, and lower government corruption. ...

...It is popular to blame these failings on the attention and resource deficits created by the Iraq war. But they are just as much the result of the black-and-white mentality that governs our approach to foreign affairs - liberal democracy or nothing. In working with periphery states, we must be willing to accept outcomes that are less than perfect. Indeed, we must be willing to accept ruling regimes that may not like us at all. We are not trying to create mini-Americas scattered across the globe; we are looking to foster stable, free countries whose people will have little interest in the repressive ideology of our enemies.

On occasion, extremist governments hostile to the existence of the United States (Hamas in the Gaza Strip) will enjoy broad popular support, but preemptive wars must become a thing of the past. We cannot say that we value freedom and then seek political change through force when the choice of the people produces regimes not to our liking. **However, the military can, and must, be used to target individuals bent on terror aimed at American interests. Furthermore, if a nation enables attacks on our homeland, as Afghanistan did under the Taliban, then we must use all necessary means to defend ourselves. On rare occasions, this will require full-out war and post-invasion reconstruction.**

...Going forward, adopting a strategy of neocontainment will entail checking Iran's expansion efforts through proxies rather than direct strikes against the country itself. Just as we limited Soviet expansion without using overt force against the Warsaw Pact, so too can we contain the Iranian regime without flying B-2s over Tehran.

Furthermore, we must institutionalize the lessons learned so painfully over seven years of war. The military must dramatically improve its nation-building doctrine, capacity, and will, acknowledging that postwar stability is much more important in the long run than is dominating the active combat phase. We remain unchallenged in our ability to win conventional military conflicts, but we must develop the language skills, cultural awareness, and civil-affairs specialists necessary to prevail in unconventional campaigns and in fighting's messy aftermath.

Our next president will inherit a nation weary of war, a world skeptical of American motives and actions, and undecided conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, the energy and excitement of a government transition offer both the outgoing and incoming administrations the opportunity to take bold steps.

On the battlefield, it is at least as important to articulate what you are for as it is to define what you are against. In a war of ideas, this is even more critical. To do this across the world, nation by nation, will take time, and that does not come naturally to our fast paced, results-oriented society. But we need to muster the requisite patience. Untold numbers of lives hinge on it.

Navy Commander Philip Kapusta is currently serving as chief of strategic plans at Special Operations Command Central, in Tampa. Marine Captain Donovan Campbell recently returned from his third combat deployment. His book, 'Joker One,' will be published by Random House in March. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the US government.![]()